Hear From the Residents

August 6, 2023

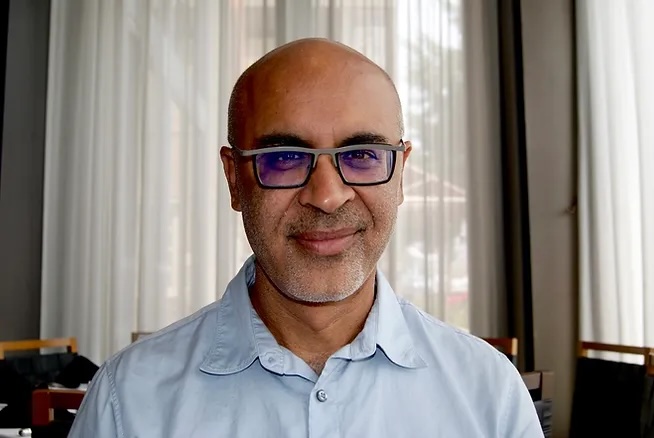

Summer Writer-in-Residence Varun Gauri: George Washington's Nelly and Her Beautiful Life

Varun Gauri’s fiction addresses migration, marriage, and other causes of madness. Born to Punjabi Partition survivors, he was gratified with his contented life in an agreeable Ohio suburb — until he recognized he wasn’t. His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and acknowledged in Best American Nonrequired Reading. His gainful employment includes research on behavioral economics and global poverty and teaching at Princeton University.

Varun Gauri is our third writer of the Summer 2023 cohort to spend a week onsite participating in our local residency program at Northern Virginia’s Woodlawn & Pope-Leighey House and Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture. Our summer writers-in-residence focus their weeks on-site exploring ways to rediscover and re-purpose place and place histories, and use writing as a means to build community, to bring awareness to critical social and environmental issues, and as a creative force of empowerment.

Elizabeth “Nelly” Parke Custis, George Washington’s step-granddaughter, raised her family alongside her enslaved individuals at Woodlawn, a plantation-estate in Alexandria, VA, which is now a museum. I spent last week in an upstairs room overlooking the museum’s finely cultivated lawns. I read Nelly’s letters and enjoyed stimulating conversations with the museum’s directors and staff.

Nelly cultivated the beautiful life, as the early Americans conceived it. She danced the minuet, played harpsichord, served delectable puddings, and showed off her French and Italian. She especially loved parties in New York with Polish and French dignitaries. Life wasn’t as fun when the American capital moved to Washington, D.C. and the family returned to Mt. Vernon, a backwater in comparison, and it was terrible after George Washington, the most important man in America, passed away and the other important people came no more. Just a couple years later, Martha Washington, more a mother to Nelly than her birth mother, also passed away. Nelly grew unhappy with her sickly and uninspiring husband, who retired to his quarters for weeks at a time. The worst, though, were the deaths of Nelly’s children, nearly unbearable for a woman as consumed by motherhood as she was. Nelly outlived, and had to bury, seven of her eight children, those little “sweet toads.”

What made a beautiful life in Woodlawn possible, of course, was slavery and the plantation economy. Nelly didn’t write much about it, though, apart from the period after Nat Turner’s rebellion, which took place nearby, and seemed to scare her. While her siblings freed many enslaved people, Nelly only liberated one, her coach driver Samuel, and did so only in her will, after she died. It seems Nelly spent her life averting her eyes from exploitation and domination (“Look away, look away, Dixie Land”), in order to make her refinement possible.

The failure to free the enslaved people at Woodlawn was morally monstrous — nearly half the enslaved were children throughout, according to historical records, which suggests the family business may have been the slave trade as much as farming. But I don’t think we can call Nelly the human being a monster, at least not without entertaining the idea that one day people might refer to us the same way. Reading Nelly’s letters, and her deepest wishes for a good life for her children, reminded me of my own striving on behalf of my own family. Our good life — desirable colleges, good cars, enjoyable vacations in exotic places. Meanwhile, a ship of migrants goes down in the Mediterranean, killing 750, including 100 children, and we do what we can to avert our eyes (I do not exclude myself here). Too much cognitive dissonance. Too many complications, and implications, if we were to look directly.

This is where my week at Woodlawn intersected with my professional life, which has focused on global poverty. There are many, many ways our personal and political choices contribute to the current suffering of individual human beings – policies restricting migration despite strong evidence that migrants would increase our own economic productivity and theirs, allocating the lion’s share of Covid vaccines to ourselves, unbridled carbon emissions, allocating our estates to those near and dear even when they do not need it, to name just a few.

I ended up writing a poem on these themes. I hadn’t written a poem in years, but it seemed a good medium for contrasting the desire for elegance with the facts of human suffering. My point of departure was a line from Elizabeth Bishop’s poem called “Poem” – “how we live, how touching in detail — the little that we get for free, the little of our earthly trust.” I think that’s what we all want – some earthly trust that abides, in this life we got for free – and what every human being, those enslaved peoples and current migrants, deserves.

Recent Posts

Summer Writer-in-Residence: Ashlee Green

Summer Writer-in-Residence: Victoria Newton Ford

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Sign up now to get the latest

news & updates from us.