Hear From the Residents

August 03, 2023

Summer Writer-In-Residence Monique Hayes: The Clock Moves Forward: How Hands Create Progress

Monique Hayes was our second writer of the Summer 2023 cohort to spend a week onsite participating in our local residency program at Northern Virginia’s Woodlawn & Pope-Leighey House and Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture. Our summer writers-in-residence focus their weeks on-site exploring ways to rediscover and re-purpose place and place histories, and use writing as a means to build community, to bring awareness to critical social and environmental issues, and as a creative force of empowerment.

Read on for a peek into Monique’s experience below.

Whenever I mention Sally Forth, I’ve always called it a novel-in-progress. However, after my inspiring week at the Woodlawn Pope-Leighey Residency, I will now proudly label it as a novel of progress.

My original plan was to write the plantation scenes for my characters first. Three of my young male slave characters come of age during the Revolutionary War on a site not unlike Woodlawn. Information carries across their fields that pause their aching fingers. Brook, Albie, and Nehemiah hear rumblings about Dunmore’s Proclamation, an integrated Continental army, and landmark court cases that secure freedom for colonial blacks. There are seeds of progress and they run towards independence. Their individual journeys mirror Woodlawn’s maturation, with its pivotal shift from a place of enslavement to a location where blacks found agency.

Woodlawn Plantation was the ideal location to visualize their everyday routines, imagine their private interactions, and devote time to their lives instead of getting distracted by mine. My characters’ days in the field were surprisingly the last scenes I wrote.

Instead, a question came to me, turning my mind’s gears. An original clock, most likely created by an enslaved craftsman, stands in Woodlawn’s entry hall. My internal voice chimed in and asked: how does it feel to be William Lee, immediately freed upon George Washington’s death, and see the dower slaves remain in bondage at Mount Vernon? How does it feel to be a manumitted slave and ordered to leave your state in 1806? Perhaps your life feels like a stopwatch rather than a running clock, where there’s movement until someone hits a button. This painful awakening set me on a new path.

Motivated by the moving clock that’s remained at Woodlawn, I wrote scenes where hands were used to show progress. Mixed-race journalist Nehemiah insists he’s creating thunderous noise when he’s working the press in Benjamin Franklin’s print shop. Papers proclaiming the work of abolitionists stream out into the world with his help.

In one of the bedrooms where Lafayette stayed, I composed a passage for Continental soldier and teacher Brook as he bids adieu to the famous Marquis. Brook traces a new trail on Lafayette’s map, distant places he’ll tell his students about in the first evening school for blacks in Philadelphia.

Finally, Black Loyalist Albie packs away his belongings to join Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, drinking in the nature he loves and darting from the prison he hates. They won’t be stopped by the limiting times. While they may only see white faces on the clocks around them, their black hands are moving at the same time and they see that there’s beauty in progress.

I spent the last two days at Pope-Leighey House, the Underwood Room, and Arcadia Farm. Though aesthetically different, all three of them are places of progress.

At Pope-Leighey, I was told that the structure was designed for homeowners with no servants, an intriguing contrast to Woodlawn. This propelled me to create scenes about Brook’s private life in Pope-Leighey’s sanctum. Newly freed after his military service, he’s living in a home without servants for the first time.

I saw children of diverse backgrounds enjoying the Arcadia Farm Camp, a girl cartwheeling towards gardens that promote sustainability and where they educate new farmers. They are the lovely reality of my future farmer Albie’s life-long dream, his children working and playing freely on a successful farm.

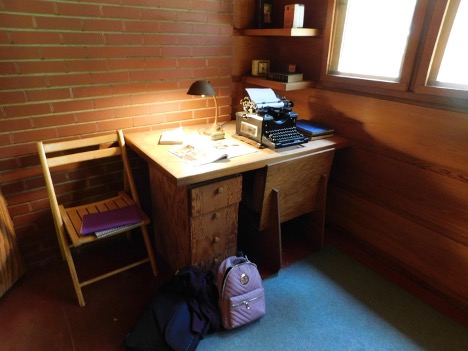

Finally, in the Underwood Room, I created my final scenes of the Residency by inhabiting a space devoted to Woodlawn’s mission to share the stories of its black communities and descendants. It was an appropriate spot to write about Brook’s visit to William Lee at Mount Vernon, with Brook telling Billy Lee about his hard-won battle for freedom, something Billy Lee receives a decade after him. Billy Lee and Brook are both natural storytellers, and the Residency certainly helped me put their voices on the page.

Progress isn’t easy, and neither is writing a Revolutionary War novel. Still, I’ve yet to stop. I thank the Inner Loop and Woodlawn-Pope Leighey staffs for letting my hands move without any interruption. I went back in time and hope these black stories will make an impact in the times to come.

Monique Hayes is a fiction author, poet, and screenwriter from suburban Maryland. A Callaloo and Hurston/Wright Fellow, she received her MFA from the University of Maryland College Park. She’s the recipient of an American Antiquarian Fellowship, an Eccles Visiting Fellowship (British Library), a Rubenstein Library/John Hope Franklin Center Travel Grant, a Ruth Stone House BIPOC Scholarship and a Maryland Independent Artist Award. She was an inaugural winner of the Courage to Write Grant (the deGroot Foundation). Her work has been short-listed for the Historical Writers Association Dorothy Dunnett Story Award, the Alexander and Dora Raynes Poetry Prize, and the Eyelands International Prize.

Recent Posts

Varun Gauri: Summer 2023 Resident

Manuela Silvestre: Summer 2023 Resident

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Sign up now to get the latest

news & updates from us.