Hear From the Residents

July 14, 2024

Summer Writer-In-Residence Amanda Borquaye: “God Bless the Yankees!”- Ideology in a Changing Landscape

Amanda Borquaye is the first writer of the Summer 2024 cohort to spend a week onsite participating in our local residency program at Northern Virginia’s Woodlawn & Pope-Leighey House and Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food and Agriculture. Our summer writers-in-residence focus their weeks on-site exploring ways to rediscover and re-purpose place and place histories, and use writing as a means to build community, to bring awareness to critical social and environmental issues, and as a creative force of empowerment.

She is a creative nonfiction writer from coastal Georgia. Her work largely focuses on exploring how the young adulthoods of her Ghanaian immigrant parents were shaped by larger systemic phenomena of colonialism, racism, sexism, and classism and what stakes those realities present for her as a second-generation immigrant. She is an alum of the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop, Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, and Lighthouse Writers Advanced Workshop. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and can be found in Roxane Gay’s Emerging Writer Series and Longleaf Review. She holds a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy and currently lives in Washington, DC where she works in international development and humanitarian response.

I arrive to Woodlawn for the first day of my residency on a debilitatingly hot day. As I sat overlooking the vast lawn from an air-conditioned office, my mind immediately shifted to those who were once enslaved here, toiling away under a similarly brutal sun without that luxury. As a second-generation Ghanaian-American, this nation’s legacy of slavery is not one my ancestors have the direct lived experience of, but it is still a history that has deeply shaped me.

Growing up, my parents would make sure my sisters and I visited Elmina Castle, a UNESCO World Heritage site in my mother’s hometown of Elmina on the coast of Ghana. It was established by the Portuguese in 1482 for trading humans as chattel as well as the extraction of our natural resources of gold and ivory. A plaque commemorates those who were held captive in the dungeons and ultimately traded across the Atlantic through the door of no return. It reads: In everlasting memory of the anguish of our ancestors. May those who died rest in peace. May those who return find their roots. May humanity never again perpetuate such injustice against humanity. We the living vow to uphold this.

I thought of this to ground myself for the week – how can we ensure memory is everlasting when only some are cast as the figures we remember and regard in American history, such as the Washington family (and by extension, the Lewises)? And what good is a vow to uphold their memories and their stories if in reality, most of the records we have deliberately disremembered them? There were some caveats to this. At orientation, we held bricks handmade by enslaved people, the swirls of their fingerprints visible from having to hand turn each brick that forms the opulent exterior of Woodlawn.

Our senses are a powerful tool for memory and can be activated to remember histories that we did not live through. I remember that the tour guides at Elmina often tell visitors not to cover their noses. As a toddler visiting for the first time, my mother rocked me back and forth while I gagged. The stench of those who defecated, bled, urinated, and sweat in agony is still present over 200 years later. It is almost impossible to process how a stench can live that long, but through that stench, we remember those who suffered there. Through a fingerprint in a brick, we remember the people exploited to build a foundation for something that is preserved despite their own history not being preserved. I wonder about the dichotomy of opulence and grandeur of exteriors that draws people in rather than the tragic histories that lie underneath that should have a repelling force. I often felt small in the grandeur and opulence of Woodlawn.

I ended up having even more questions than I set out with to examine. What institutions or ideologies are people willing to die for (such as the Confederacy)? Who gets to be a visionary? For oppressed people, imagined futures are a source of reclaiming agency, but so often for those in power, envisioning the future is a strategic blueprint of how to capitalize on and maintain power for generations. And how does land play a role in power? Do people belong to land, or does land belong to people? Land is routinely objectified and commodified, projected onto as a blank canvas upon which one can manifest their quest for domination, which necessitates another’s subjugation.

I wanted to see if there was another narrative about land I could find at Woodlawn, one that saw land and nature for their potential to liberate rather than subjugate. This led me to the journals of a meticulous man named Chalkley Gillingham, a Quaker settler who purchased 2,000 acres of Woodlawn in 1846 with other Quakers. There’s a particularly interesting entry from his journal in their early days of settling at Woodlawn:

We now have a store, school, smith shop and Meeting and are raising fine crops of grain and hay. We find no difficulty in getting along without the use of slave labor. This was one object in coming here, to establish a free labor colony in a slave state. It works quite well as we expected and the influence it exerts upon the laboring population is very encouraging – elevating them to a much better condition than they were before our establishment went into operation.

Yay, the Quakers have successfully transformed a slave operation into what sounds like a bustling community where Black laborers are compensated for their work! But even in this visioning, the ills of the previous settlers’ ideologies are discernible. Gillingham and his peers still adhered to a colonial mindset of “colonizing” the land, and even in the aforementioned passage, the politics sound more akin to white saviorism than radical liberation. Perhaps my favorite part of his journal is an anecdote he shares of a Black woman visiting their sawmill and exclaiming to him, “God bless the Yankees! I wish more of them would come here.” It’s hard to know if this actually occurred or was an embellishment, but this again seems to demonstrate that though no longer enslaved, Black people now dealt with a new group of settlers who believed their wellbeing was due to the Godsent Yankees. While their agency increased in one way, the shifting ideology of the land and those asserting themselves as the visionaries of it still reeked of colonialism, although a gentler, paternalistic iteration.

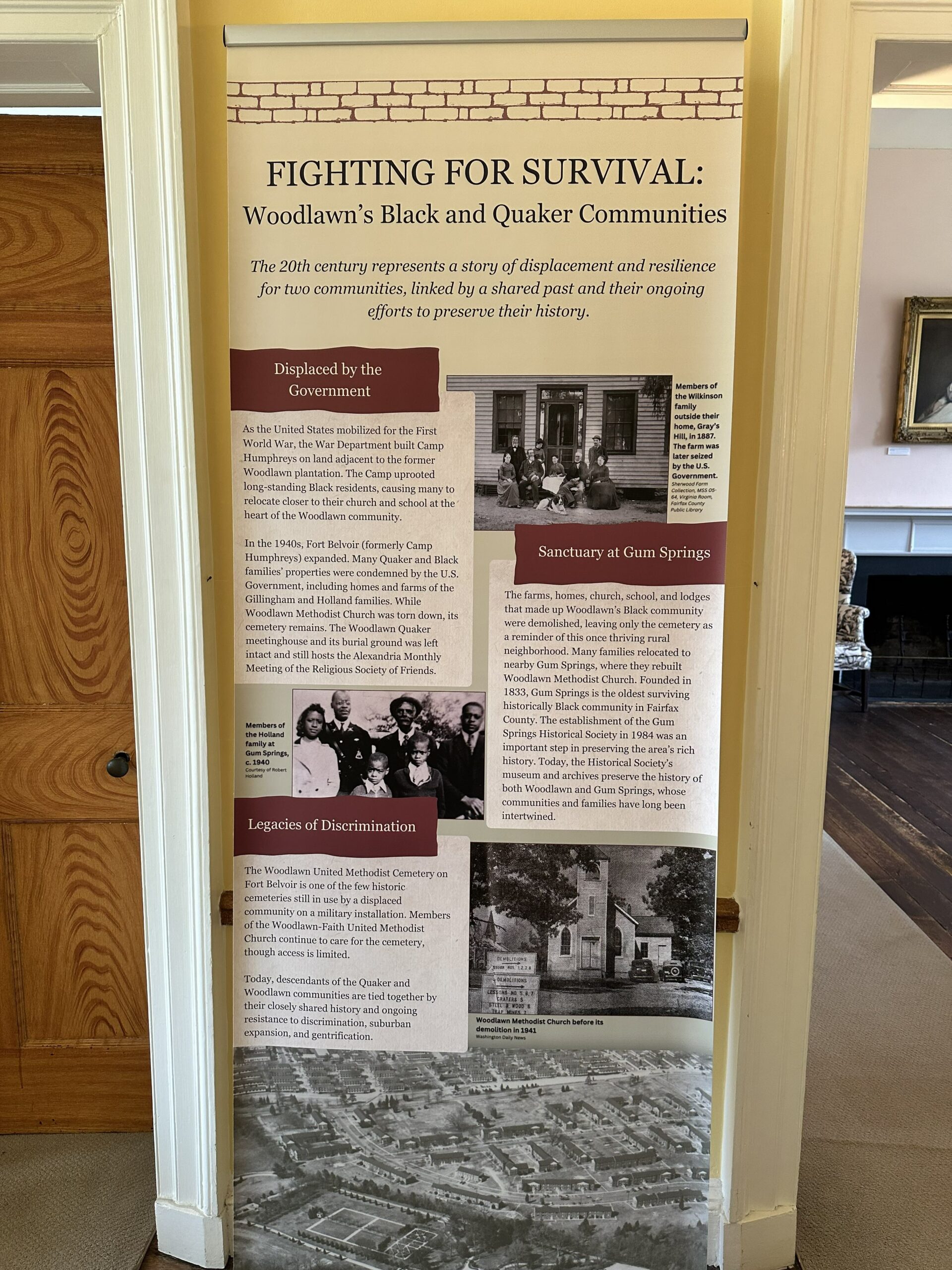

If we fast forward to today, the land is evolving yet again. I pace through the mansion and find carefully researched exhibits about the native Doeg population that was displaced. There’s an exhibit acknowledging the romanticization of plantations like Woodlawn, of how these sites can reproduce myths and cast white settlers as legends. I have hope in the new custodians and visionaries of Woodlawn. Just as Woodlawn was built brick by brick, our understanding of it will continue to be rebuilt overtime.

Recent Posts

Varun Gauri: Summer 2023 Resident

Monique Hayes: Summer 2023 Resident

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Sign up now to get the latest

news & updates from us.